Risk Factors and Clinical Management of Open-Angle Glaucoma: Two Case Studies

Purpose. The aim of this paper is to discuss and highlight the interpretation of two risk factors; corneal hysteresis and pigment dispersion syndrome, as they relate to the development and management of open-angle glaucoma using two clinical cases diagnosed and treated at a glaucoma clinic in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Material and Methods. A case suspicious for glaucoma is presented with additional risk factors and ancillary testing evaluated, ultimately leading to its diagnosis. A secondary case is presented of a secondary open-angle glaucoma, demonstrating its key anatomical characteristics and treatment approach.

Results. In the first case, corneal hysteresis and its interpretation was found to be an additional risk factor aiding in the diagnosis of glaucoma along additional well-accepted risk factors. In the second case, a currently treated case of pigmentary glaucoma is reviewed and differentiated from different forms of glaucoma and supplemental treatment is initiated due to progression via structural and functional testing.

Conclusion. Earlier diagnosis of glaucoma was achieved due to identification of the additional risk factor of low corneal hysteresis, and identification of progression in an already treated case of secondary glaucoma results in adjunct treatment.

Introduction

Glaucoma is a leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide affecting close to 80 million people as of 2020 and is projected to affect upwards of 120 million by 2040.1,2 As newly identifiable risk factors are discovered in those at risk for glaucoma, physicians will better be able to diagnose and treat sooner, preventing potential damage and overall blindness of individuals. Recognizing the differential diagnoses of open-angle glaucoma and identifying key features of secondary glaucomas can support earlier detection and help prevent permanent vision loss. This case report details two cases involving risk factors for glaucoma and discusses the key clinical findings.

Case 1

A 70-year-old black female presented to a specialty eye care clinic in Philadelphia. She was referred from her family optometrist for suspicion of glaucoma based on large optic nerve cup size, positive family history and mildly elevated intraocular pressures. The patient‘s medical history did not indicate any significant findings. She reported no history of hypertension or diabetes, and there were no known drug allergies. Visual acuity with current correction in the right and left eye was 20/30. Entrance testing was unremarkable and included confrontation fields, extraocular motility and pupillary assessment. Slit lamp examination revealed 1+ nuclear sclerosis in both eyes.

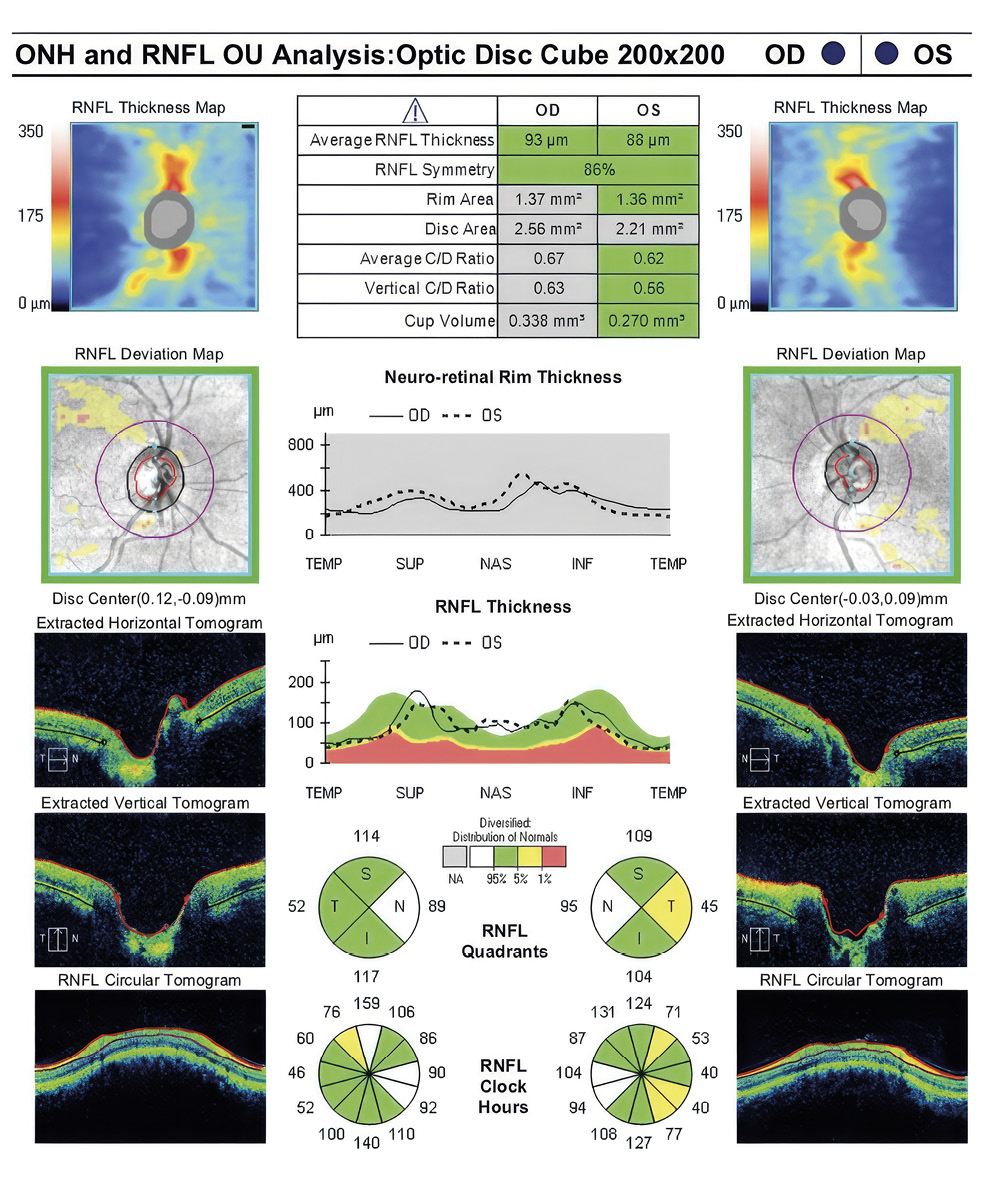

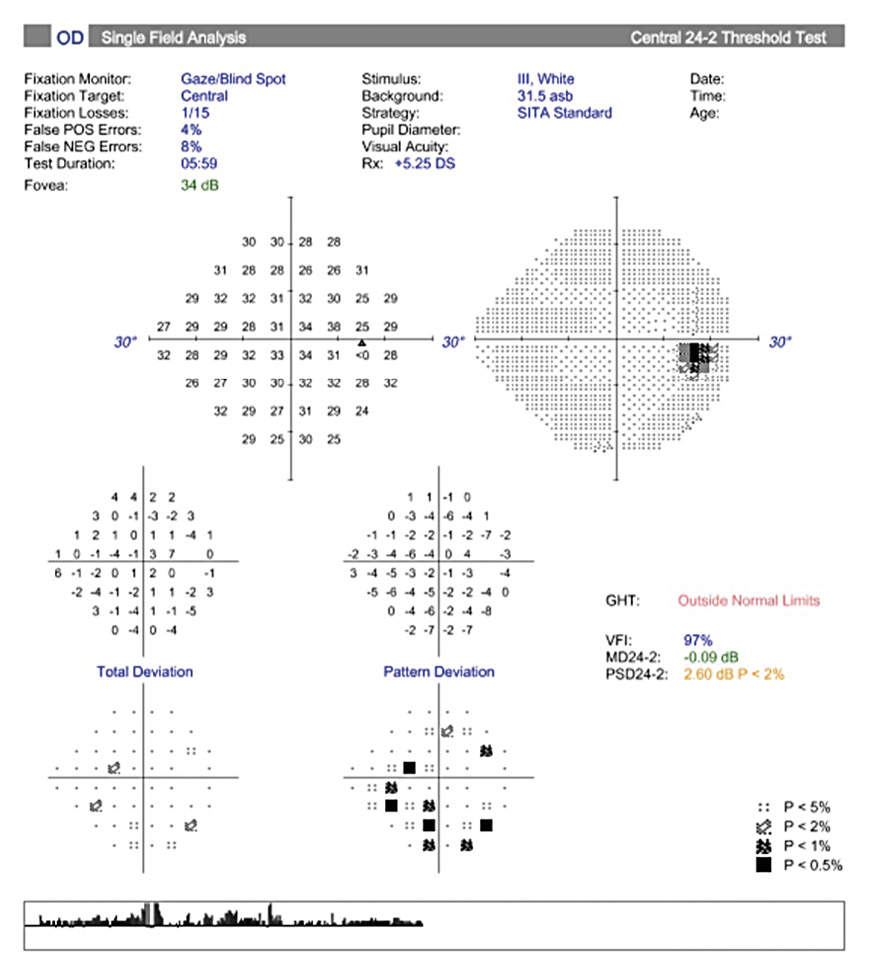

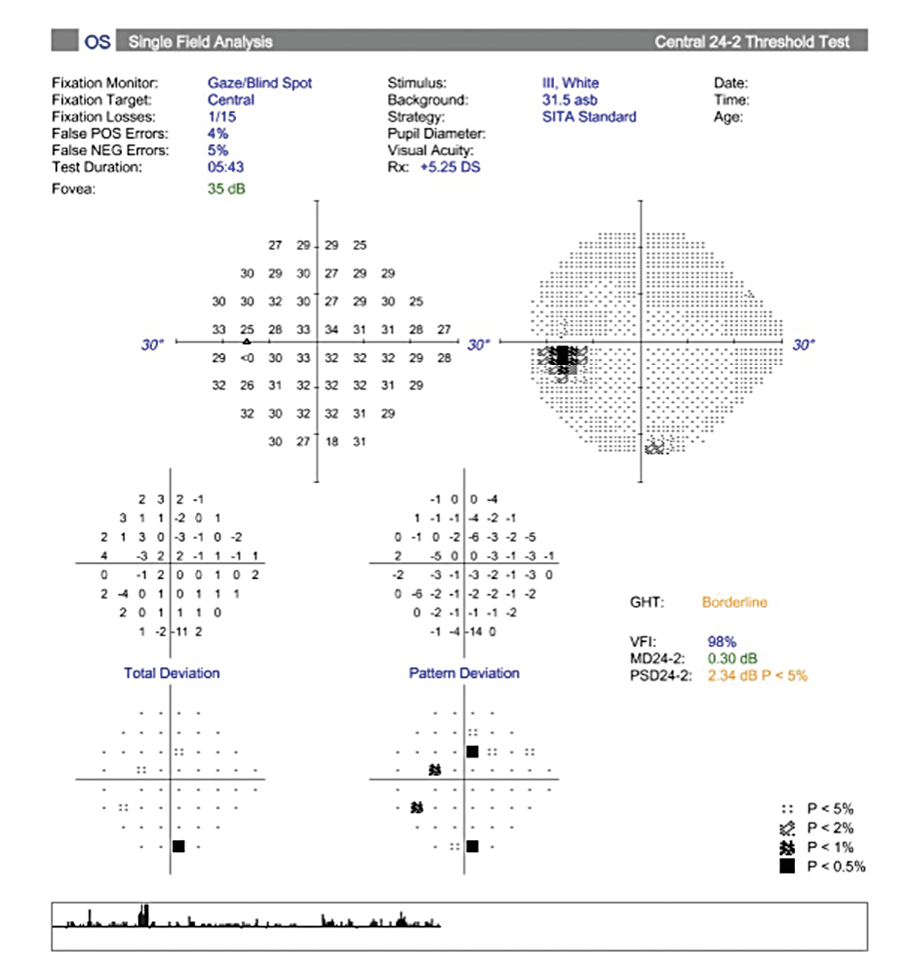

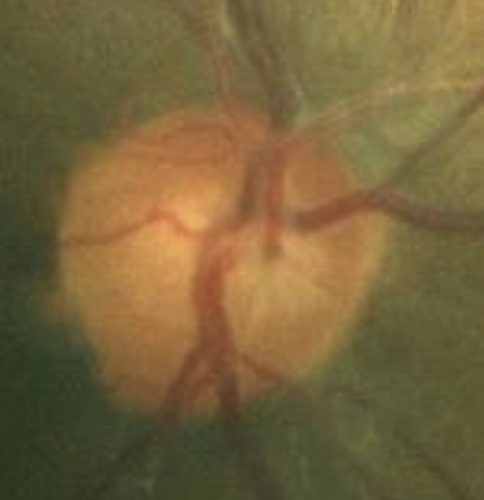

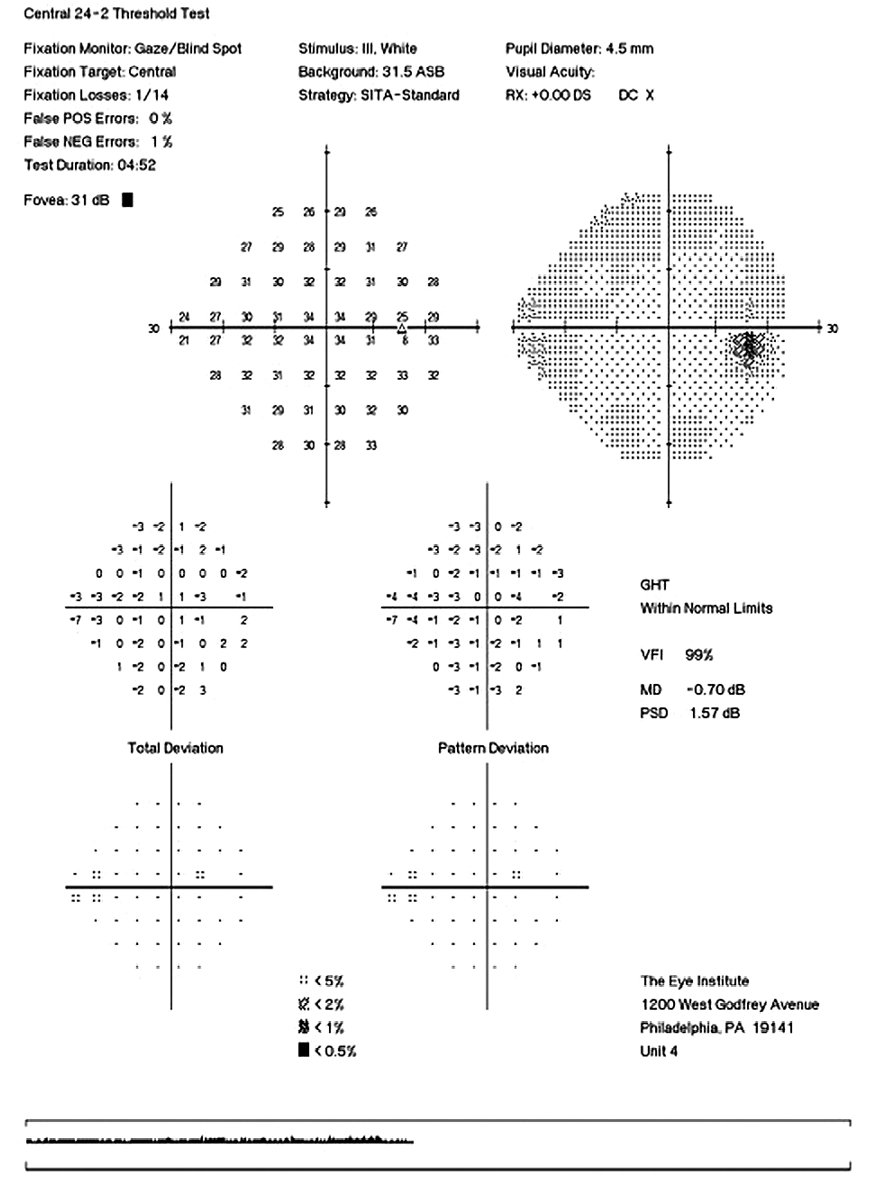

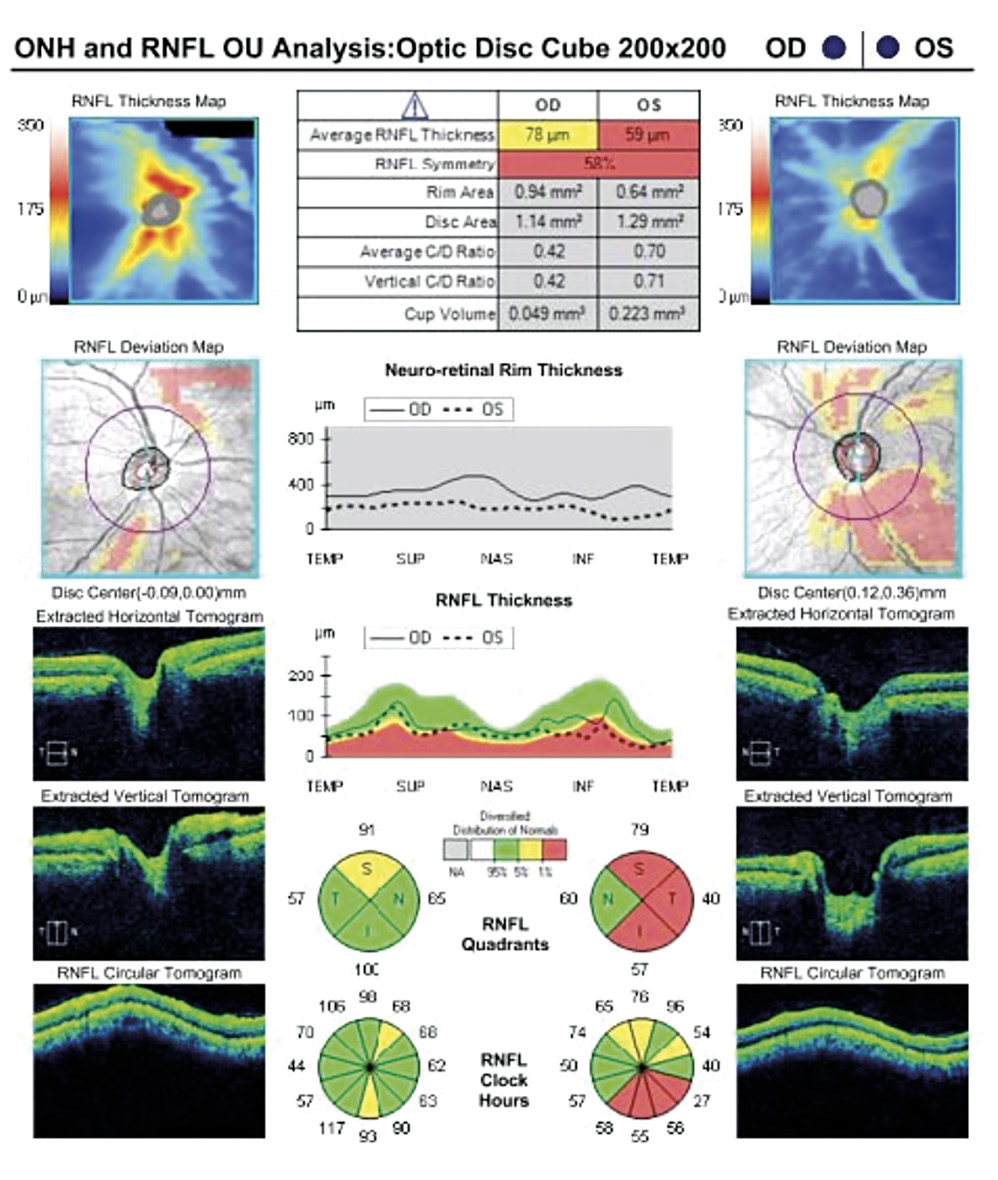

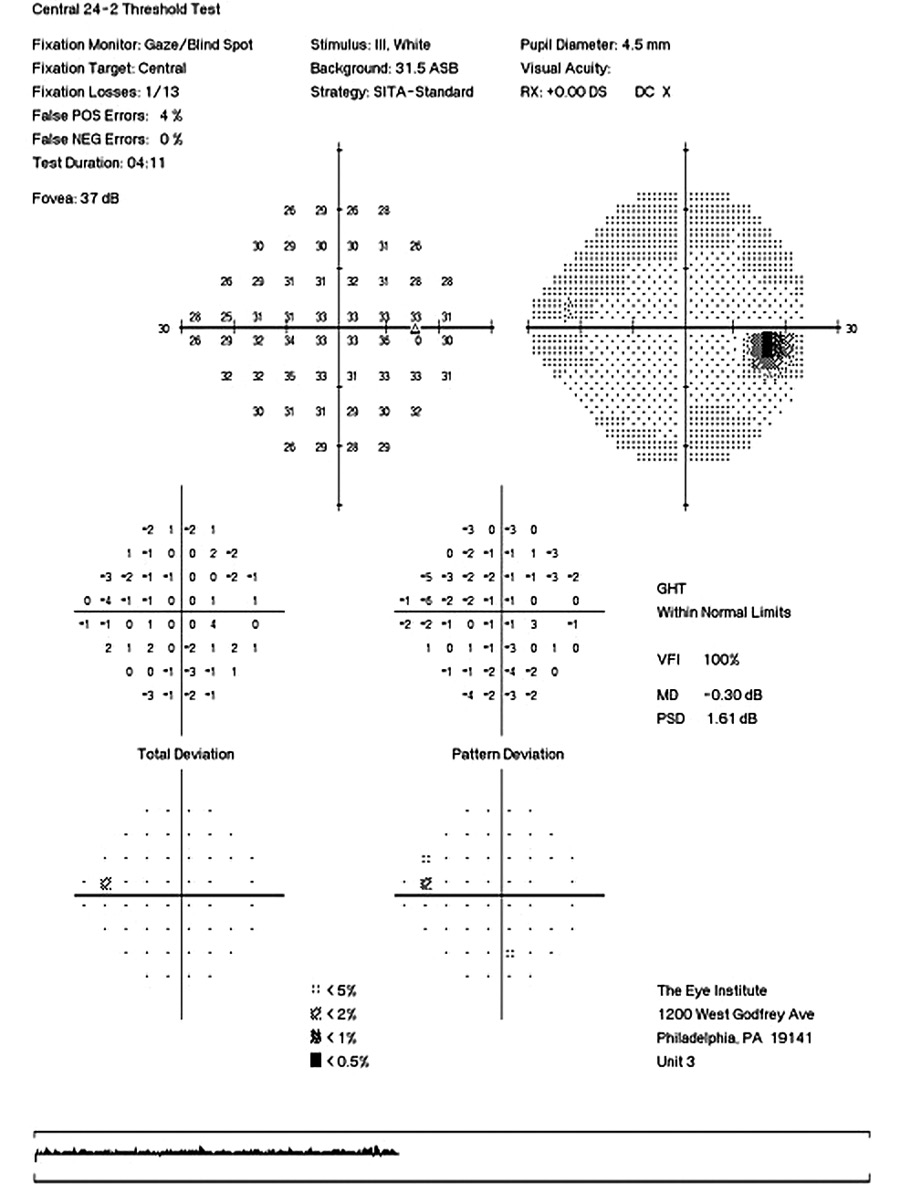

Her intraocular pressure was measured via Goldmann applanation tonometry (GAT) at 26 mmHg in both eyes at 10:15 am. Intraocular pressure was remeasured via iCare with values of 33 mmHg in each eye. Gonioscopy confirmed open anterior chamber angles and demonstrated no secondary causes for the elevated eye pressure. Assessment of the optic nerve showed an intact and well-perfused neuroretinal rim in both eyes, with normal optic nerve head morphology. Central corneal thickness measurements (CCT) were also measured via optical coherence tomography (OCT) and measured 589 microns OD, 598 microns OS. Baseline optic nerve head OCT, optic disc photos and 24-2 Humphrey Visual Fields were obtained (Figures 1, 2, 3).

Visual field testing showed a GHT (Glaucoma Hemifield Test) in the right eye outside of normal limits due to a significant difference in amount of depressed points in the inferior versus the superior hemifields and a borderline GHT in the left eye. The OCT findings of the optic nerve head and retinal nerve fiber layer showed superior and inferior quadrants, specific to glaucoma, within the distribution of normals in both eyes.

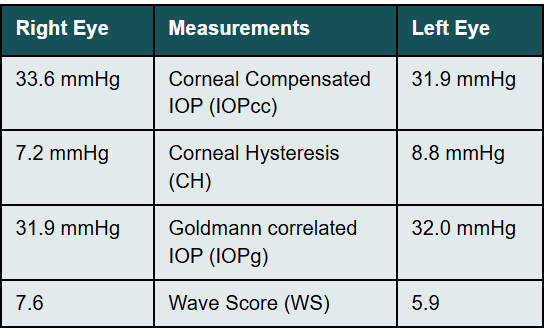

Additional intraocular pressures were measured via an Ocular Response Analyzer (ORA) (Reichert Technologies, Depew, NY, USA). Findings are shown in Table 1 below:

Corneal Hysteresis (CH) in this case was measured at 7.2 mmHg OD & 8.8 mmHg OS. Both values being less than 10 mmHg and considered to be a significant risk factor for progression to open-angle glaucoma.3 Based upon the elevated intraocular pressure, low CH, race, and borderline visual field studies, a diagnosis of mild primary open-angle glaucoma OU was made. As a newer tool in the assessment of individuals risk for all glaucomas, CH aided greatly in the early diagnosis of glaucoma in this case. Treatment was initiated with a prostaglandin analogue for both eyes to be taken nightly. Follow up for efficacy was scheduled for 4-6 weeks from this visit.

Discussion

Many risk factors have been identified and are well accepted in patient evaluation for development of glaucoma. Risk factors for glaucoma according to the European Glaucoma Society (EGS) include: age, intraocular pressure, race/ethnicity, positive family history, evidence of pseudoexfoliative material, CCT, myopia, ocular perfusion pressure, diabetes, systemic blood pressure, Raynaud syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea.4 As additional risk factors begin to be identified, our patient assessment and detection of glaucoma will become earlier in the course of the disease, allowing us to further slow preventable blindness from glaucoma.

The Ocular Response Analyzer (ORA) (Reichert Technologies, Depew, NY, USA) is a non-contact tonometer developed in 2005 where an air-puff is emitted in a similar fashion to a traditional non-contact tonometer except air continues to be emitted until the cornea is indented, then decreases until the cornea rebounds back to normal in approximately 20 milliseconds.5 This corneal deformation is measured via an electro-optical infrared detection system until it deforms back to its original shape.6 The difference in the pressures helps to measure CH and is found to be less dependent on central corneal thickness measurements.7 GAT readings are influenced by corneal hydration, rigidity as well as CH. By obtaining CH measurements you can obtain a pressure reading less influenced by these corneal properties via the IOPcc (corneal compensation).8 Obtaining CH readings via the ORA in all patients at risk of glaucoma as well as those already being treated for glaucoma will better aid in the initial diagnosis and ensure adequate long-term treatment.

CH is a viscoelastic property of the cornea; the term originates from Greek, meaning „lagging behind“. CH can be thought of as the viscous damping ability of the cornea and characterizes how it handles external stressors.9 Similar to how concrete versus wood versus titanium have different properties when it comes to deforming and reforming after a force is applied to the material. This property of the cornea is considered an added risk factor for glaucoma when values are measured below 10 mmHg.10,11,12,13,14 CH is independent of central corneal thickness (CCT), and a greater corneal thickness does not necessarily correspond to higher CH values; likewise, lower CCT measurements do not imply reduced CH.15,16,17,18,19

In this case, the patient’s CCT was thicker than average given her untreated IOPs via GAT of 26 mmHg OU.20 Although IOP correction calculations exist for CCT values outside the normal range, there is no widely agreed upon calculation and the IOP readings are to be interpreted as being an overestimation of the patient’s true IOPs.

CH and its biomechanics properties have been found to be lower compared to same age normals and has been identified in various forms of glaucoma including primary open & closed angle, normal-tension as well as pseudoexfoliative. 21,22

A lower CH has also been found to be associated with an increased risk of progression in glaucoma although no true causal relationship has been shown. Despite this, it is still widely accepted that measurement of CH aids in the overall assessment of ones development of the disease as well as an additional tool in monitoring patients afflicted by the condition in additional to the traditional structural and functional testing that is already being performed on all glaucoma and at risk for glaucoma patients.21

The thought behind why there is a correlation of higher glaucoma prevalence with lower CH readings is theorized to be due to the properties of the cornea, namely a low CH, which may translate to similar characteristics at the level of the sclera and thus the lamina cribrosa.23,24 This helps to explain why even small fluctuations in IOP may still result in damage to the optic nerve, specifically in cases of normal tension glaucoma. CH has been found to be low (< 10 mmHg) in patients with glaucoma regardless of IOP level.24,25 This suggests a pressure dependent additional risk factor and an additional piece to the puzzle to aid in earlier diagnosis of glaucoma.

CH is a relatively new exam element to aid the clinician in their assessment of patient’s risk of glaucoma development. Obtaining an ORA reading is fast, well-tolerated and easy to interpret. When assessing an individuals risk for development of glaucoma, many factors exist needing thorough evaluation. With the identification of newer risk factors such as CH, an earlier diagnosis of glaucoma can be made and thus treatment of the disease can be initiated earlier in the course of the disease leading to less likelihood of blindness as the condition transpires. This case demonstrates use of CH as an additional clinical tool to aid in the earlier detection and treatment of glaucoma.

Case 2

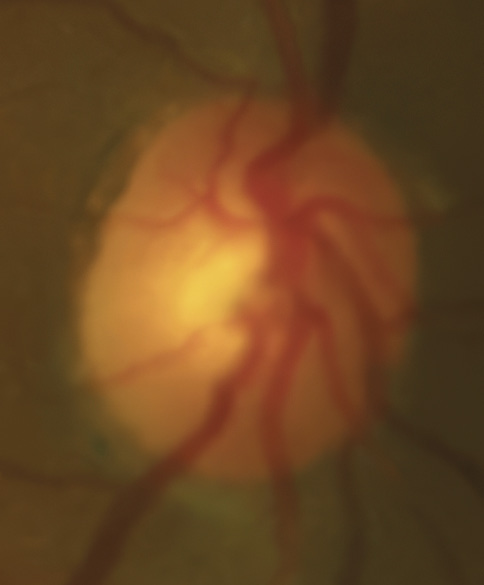

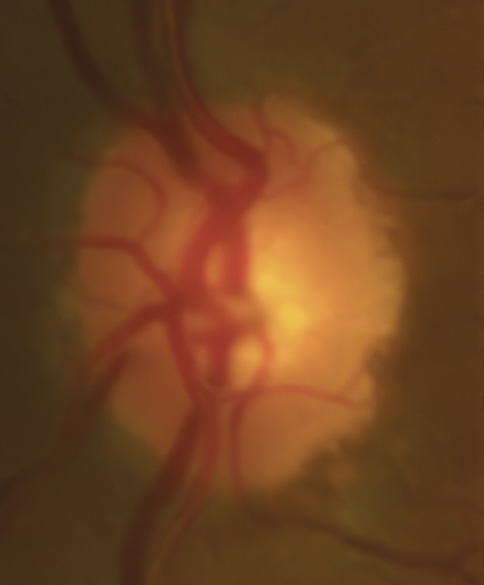

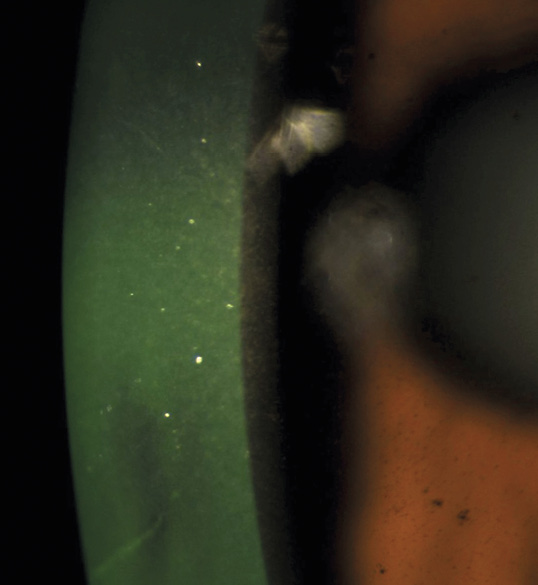

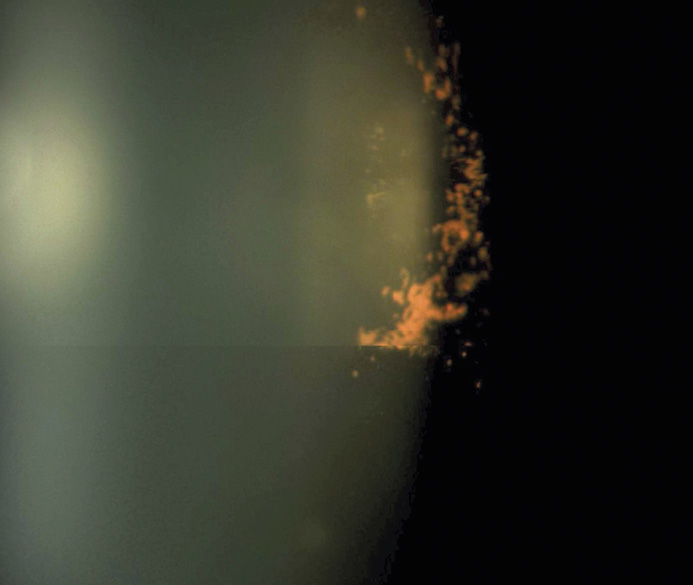

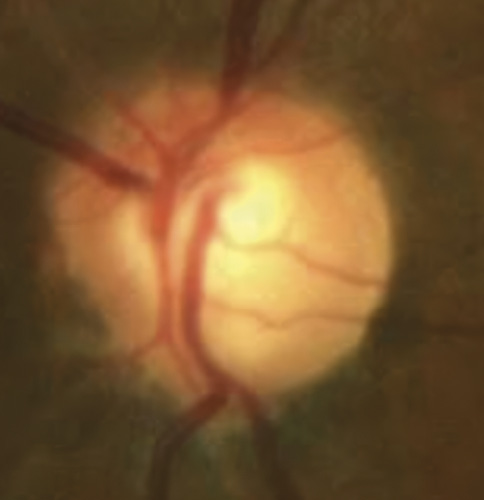

A 46-year-old African American male presents for glaucoma quarterly monitoring. Medical history is positive for hypertension controlled with 50 mg hydrochlorothiazide and reports no diagnosis of diabetes mellitus or known drug allergies. Ocular history is positive for progressive myopia bilaterally and pigment dispersion syndrome converting to pigmentary glaucoma right eye mild, left eye moderate with treatment initiated in September of 2016. The pigmentary glaucoma was treated with 0.005% latanoprost in both eyes every evening. There was positive family history of glaucoma (patient’s father). Best corrected visual acuity was measured at 20/25 in each eye. Pupillary assessment revealed a stable 1+ afferent pupillary defect in the left eye. Confrontation fields were full to finger count in the right eye and superonasal constriction in the left eye. Extraocular motilities were full with no restrictions or report of diplopia in both eyes. Slit lamp examination is remarkable for a Krukenberg spindle (Figure 4) bilaterally and a Zentmeyer line (Figure 5) in the left eye. Intraocular pressures at 3:30 pm via GAT measured 18 mmHg right eye, 23 mmHg left eye. Gonioscopy was performed and revealed open angles to ciliary body with a concave iris configuration and 4+ trabecular meshwork pigmentation (Figure 6) and the posterior corneal surface. There was no pigment attached to the anterior lens surface. The highest recorded intraocular pressures prior to treatment were 27 mmHg right eye & 35 mmHg left eye. CCT measured 554 microns in the right eye and 538 microns left eye. Optic nerve head assessment revealed bilateral intact neuroretinal rims with vertical elongation greater in the left eye than the right with inferior neuroretinal rim thinning in the left eye (Figure 7).

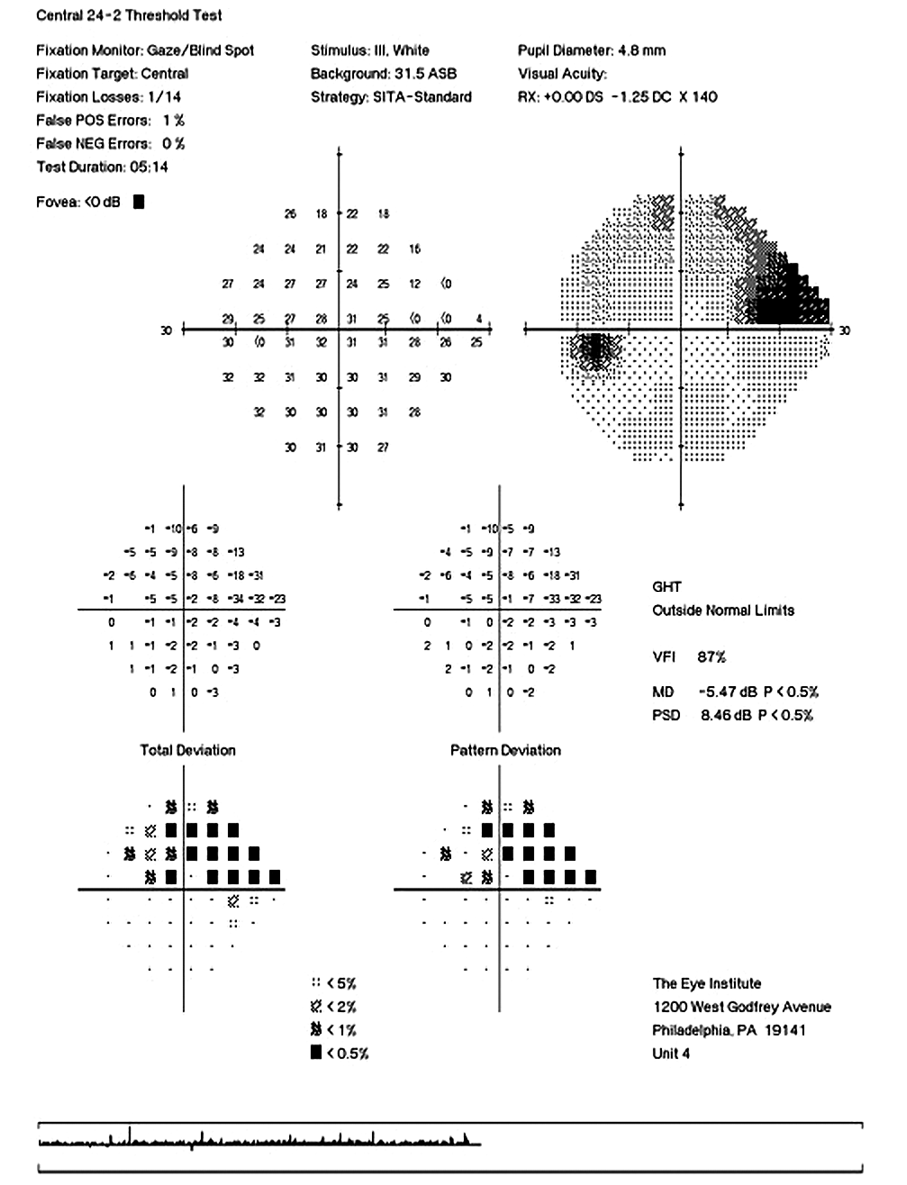

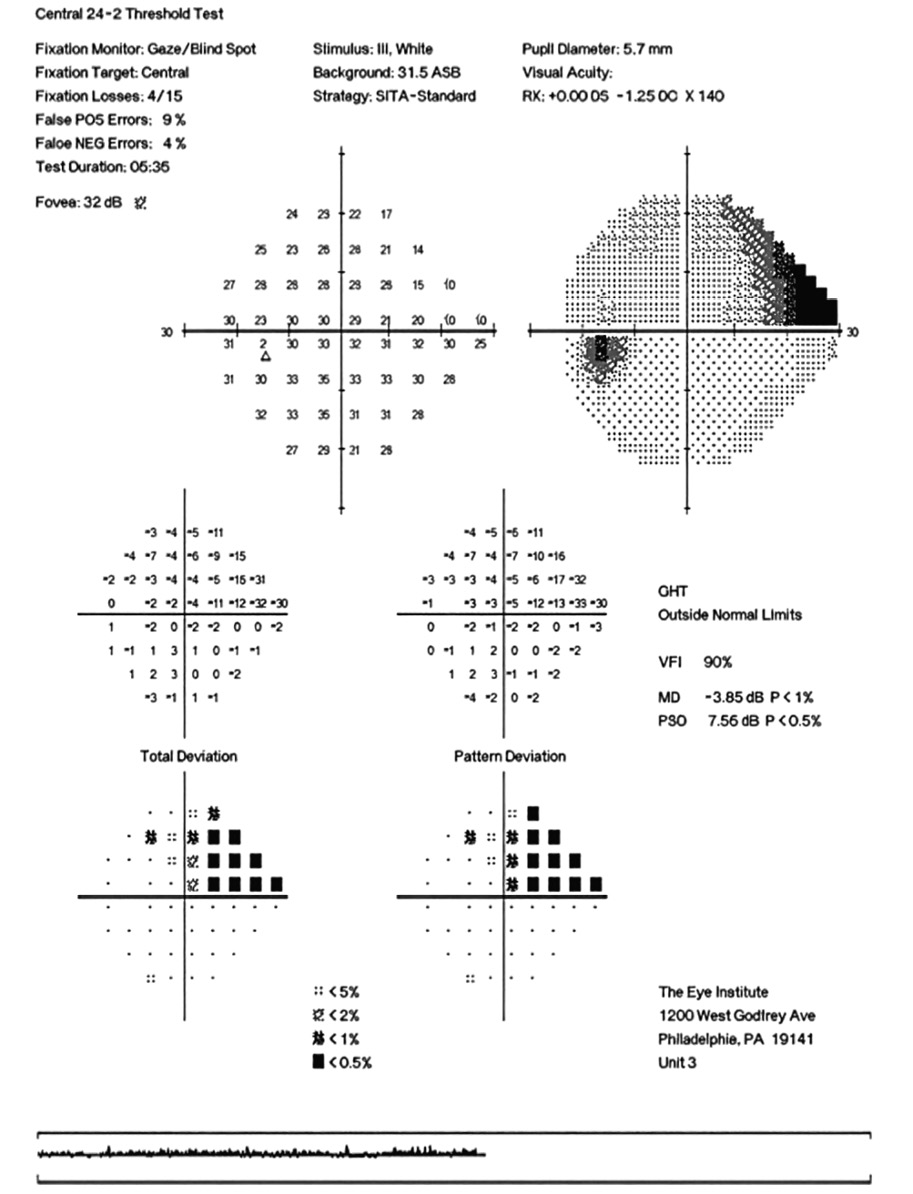

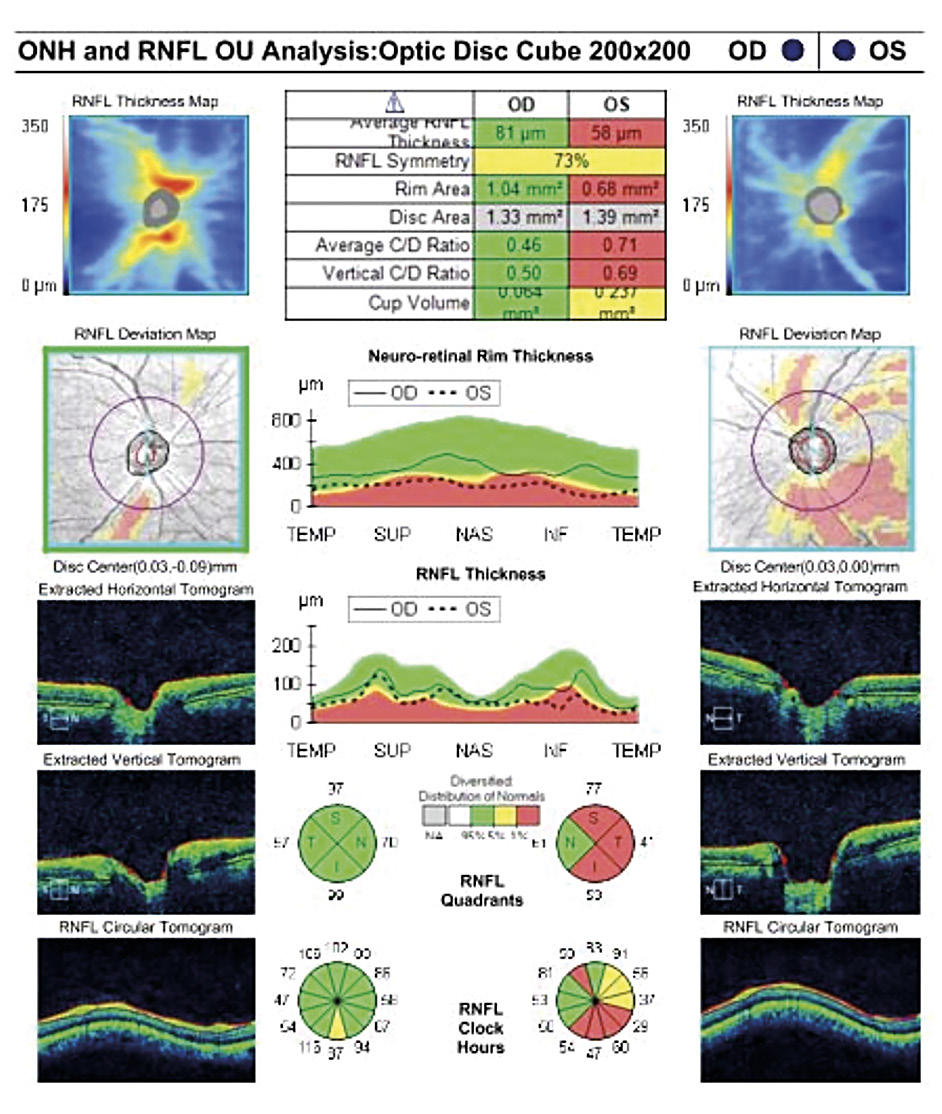

CD ratios were estimated horizontally/vertically as 0.4/0.5 right eye, 0.6/0.8 left eye. Repeat testing of 24-2 Humphrey Visual Fields (HVF) (Figure 8) and optic nerve head optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Figure 9) were obtained.

Slight functional progression was noted of the left visual field compared to previous over a 1 year period (Figure 10) as well as OD > OS structural progression on OCT (Figure 11). Current percent IOP reduction from baseline was calculated to be 34 % OD & 35 %. Due to the degree of damage with functional loss via a nasal step in the left eye, it was determined that greater percent IOP reduction be achieved, specifically 40-50 %.26,27 Additional treatment was initiated of 2 % dorzolamide BID OU. The patient was scheduled to return in 6-8 weeks to monitor efficacy of newly prescribed medication. At follow up patient reported good compliance with 2 % dorzolamide BID, intraocular pressures to be 14 mmHg OD & 16 mmHg OS via GAT. The patient was scheduled to be re-evaluated again in 3 months for continued monitoring after an additional 20-22 % IOP reduction was achieved, resulting in a total IOP reduction of 48 % and 55 % from baseline untreated IOPs.

Discussion

Pigment dispersion and subsequent elevated intraocular pressure occurs when melanin pigment from the posterior iris epithelium becomes liberated within the anterior chamber. This liberation occurs due to the mechanical rubbing of the posterior iris epithelium with the lens zonules via a concept known as iridozonular contact.28,29 The specific orientation of the iris plays a key role in the contact between the zonules and iris epithelium and may relate to the patient’s refractive error, commonly seen in patients with larger magnitudes of myopia.30 Because of this, it is important to conduct a thorough anterior segment assessment and if warranted, gonioscopy in all myopic patients. The posterior bowing or concavity of the iris promotes the peripheral contact between the two structures especially during times of increase sympathetic tone resulting in pupillary dilation as well as prolonged near work with associated miosis and overall iris mobility.28,31,32,33 Due to these momentary bouts of pigment dispersion, IOP may not be elevated in office when examining these patients, however damage may be apparent when evaluating the optic nerves of these individuals. This liberation of pigment experienced by the patient may result in temporary blurred vision, a phenomenon described as a “pigment shower”.30 Liberated pigment granules can then cause impedance of aqueous outflow by way of accumulating within the trabecular meshwork (TM) after making its way from the posterior chamber to the anterior. In some cases, the blocked meshwork will result in a significant spike in intraocular pressure (IOP) and subsequent glaucomatous damage where aggressive glaucoma treatment is indicated due to the transient nature of the elevated IOP.29

There exists 3 forms of pigment dispersion: Pigment Dispersion Syndrome (PDS), Pigmentary Ocular Hypertension (POH) and Pigmentary Glaucoma (PG). PDS can be defined as iris pigment dispersed throughout the anterior structures of the eye and can result in either POH or PG. POH is the presence of pigment within the anterior structures of the eye with subsequent elevation of IOP but no evidence of glaucomatous optic neuropathy. The last form, PG, occurs through the same mechanism as POH but with signs of glaucomatous findings.34 While sometimes not readily apparent due to a normotensive IOP reading, knowledge of the key anatomical characteristics of PDS at the level of the anterior chamber as well as assessing the optic nerve appearance can cue the clinician in to making the proper diagnosis of PG as opposed to the potential of it being masqueraded as primary open-angle glaucoma. The case discussed in this report is one of PG where additional treatment was indicated due to structural and functional progression.

Key features within all forms of pigment dispersion display areas of the anterior eye where pigment has either deposited or has been lost. These findings include mid peripheral iris trans-illumination defects in a spoke-like fashion, vertical deposition of pigment on the corneal endothelium known as Krukenberg spindles, a heavily pigmented TM observed on gonioscopy, pigment depositing on the posterior lens surface known as Zentmayer’s line and pigment settling at the junction of the zonules and posterior capsule termed Scheie’s stripe.34 More recently, the use of ultrasound biomicroscopy and anterior segment OCT has aided in the identification of concave iris configurations where it is not as readily apparent on slit lamp and gonioscopic evaluation alone.35

Despite all these features of PDS, it is important to discern cases of glaucomatous processes from others of nothing more than liberated iris pigment or instances of trauma. This includes a lack of anterior lens pigmentation, specifically in a radial like fashion that would suggest an instance of trauma and thus confound a singular diagnosis of pigment dispersion syndrome and/or glaucoma.36

The typical demographic features of both PDS and PG tend to overlap in characteristics. Both PDS and PG predominantly affects the Caucasian race and occurs in the early to middle decades of life, 20 to 40 in PDS and 30 to 50 in PG.28,34 Gender predominance is fairly equal in PDS, however there is a higher prevalence of males affected by PG.28 It can also be said that family history of glaucoma may play a role in conversion but is more theorized as a general susceptibility to develop glaucoma and is not deemed to be specific to PG.34

Conversion rates of PDS developing into PG by multiple sources report a 5-10 % conversion at 5-6 years, 15 % at 15 years and 35 % at 35 years.29,34 To date there have been no large population-based surveys to further support these figures. This can mostly be explained by the low rate of PDS detection paired with the higher detection of PG or POH alone.

When treating POH or PG the approach is similar to that of other chronic, non-acute glaucomas however due to its nature of transient pigment showers during times of sympathetic activity or iris movement, these bouts may be more damaging to the optic nerve compared to a sustained elevated IOP and more aggressive treatment should be employed.29,30 Initial therapy, as in this case, of a prostaglandin analogue is typically the mainstay due to it’s efficacy, once daily administration and high safety profile. When additional therapy is indicated it is reasonable for the clinician to consider an additional medication or selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT), specifically if the patient displays non compliance while taking one medication. SLT is an effective non-medication treatment option in open-angle glaucomas. SLT works via the biologic theory, where activation of ones own immune system results in the recruitment of inflammatory mediators via sub-lethal photothermolysis of the melanin granules in the posterior trabecular meshwork results in reduction of IOP via increased outflow.37 When considering SLT for PG, the clinician must keep in mind that excess inflammation can result if all four quadrants are treated and may choose to only treat 2 quadrants or 180 degrees.38,39 If the patient demonstrates good compliance with one medication, it is reasonable to start a second medication. Studies have shown topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as 1 % Brinzolamide or 2 % Dorzolamide to be a highly efficacious 2nd line of therapy. IOP reduction of 1 % Brinzolamide has been shown to range from 16-19 % and 17-20 % with 2 % Dorzolamide.40 When treating a potentially aggressive form of chronic glaucoma such as PG, high drug efficacy is vital in order to adequately control IOP and minimize the rate of progression of the disease.

Pigmentary glaucoma is caused by a distinctive anatomical arrangement where the iris‘s posterior surface rubs against the zonules, releasing pigment that clogs the trabecular meshwork which may result in elevated IOP. Patients may experience „pigment storms,“ or increased intraocular pressure, following exercise or prolonged accommodation. The condition typically lessens with age as the natural thickening of the lens reduces contact between the iris and zonules, thereby decreasing pigment dispersion.

Conclusion

CH, a measure of the cornea‘s ability to absorb and dissipate energy, is a relatively new tool that aids clinicians in assessing a patient‘s glaucoma risk. A low CH, obtained through a fast and well-tolerated ORA reading, has been shown to correlate with a higher risk of developing glaucoma and disease progression. Pigmentary glaucoma is a secondary open-angle glaucoma caused by friction between the iris and lens zonules, which releases pigment that blocks the eye‘s drainage system and can lead to elevated intraocular pressure where aggressive treatment could be indicated due to its nature of developing transient spikes that can be more damaging than a sustained elevated IOP. The cases presented help to exemplify just some of the examples of the array of tools and assessment techniques at present to adequately diagnose early glaucoma and best identify secondary glaucomas and treat accordingly.

Conflict of interest

The authors declares that there is no conflict of interests regarding the methods and devices mentioned in the article.

Am. J. Ophthalmol., 153, 840–849.

Corneal hysteresis measured with the ocular response analyzer in normal and glaucomatous eyes. Acta Ophthalmol., 88, 116–119.

(2006). Central corneal thickness and corneal hysteresis associated with glaucoma damage. Am. J. Ophthalmol., 141, 868–875.

Richter, G. M., Ou, Y., Kim, S. J., WuDunn, D. (2023). Corneal Hysteresis for the Diagnosis of Glaucoma and Assessment of Progression Risk: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology, 130, 433–442.

(2003). What is the risk of developing pigmentary glaucoma from pigment dispersion syndrome? Am. J. Ophthalmol., 135, 794–799.

glaucoma: a review and update. Int. Ophthalmol., 39, 1651–1662.